History along the Great Allegheny Passage

The historic Great Allegheny Passage isn’t just a path through the woods. The 10-foot-wide multipurpose trail is built on railroad corridors constructed to heavy-duty standards of gentle grades, sweeping curves and major bridges and tunnels that take you through the mountains, not over them.

Along this path from Cumberland, Maryland to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Passage crosses the Mason-Dixon Line, the Eastern Continental Divide and runs through spectacular water gaps and gorges, often through miles of near-wilderness. On the trail, you’ll cycle past sites of long-cold iron furnaces and coke ovens and a modern steel mill; dozens of worked-out coal mines and even through a couple of dairy farms.

Along this path from Cumberland, Maryland to Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the Passage crosses the Mason-Dixon Line, the Eastern Continental Divide and runs through spectacular water gaps and gorges, often through miles of near-wilderness. On the trail, you’ll cycle past sites of long-cold iron furnaces and coke ovens and a modern steel mill; dozens of worked-out coal mines and even through a couple of dairy farms.

It’s a journey through time from some of the oldest rock strata to the youngest; ride the pathways of Native Americans and invading Colonial armies; follow the history of transportation from the first National Road to canals to railroads to superhighways; see the march of progress from a mercantile society to the early industrialization of coal mines and iron-works to the environmental recovery of the post-industrial era.

Along the Great Allegheny Passage, you’ll learn the whole story of the region, sometimes standing on the exact spots where history happened. Along this quiet forested path, you’ll be at leisure to pause, step back and gain a sense of place that you can’t experience any other way.

A Natural Geology Classroom

Between the coastal plain and the Piedmont to the east and the great Mississippi Basin to the west, the Allegheny Mountains have presented a formidable barrier since man first set foot in this part of the continent.

Between the coastal plain and the Piedmont to the east and the great Mississippi Basin to the west, the Allegheny Mountains have presented a formidable barrier since man first set foot in this part of the continent.

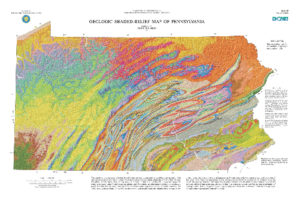

Once upon a time, the Alleghenies were a high mountain range, but millions of years of erosion wore them down to the rounded domes they are now. Sediment from the old mountains washed down in ancient westward rivers into a great inland sea that rose and fell as climate changed.

As time passed, ocean floors became limestone; shale and siltstone settled out in quiet waters of coastal bays; vegetation in warm coastal swamps became coal; river channels, dunes and beaches along the coastal plain became sandstone. In the last million years, a series of ices ages eroded the once-flat landscape to give us our now-rugged topography.

A great example of erosion at work is the “Indian Post Office” near Cedar Creek Park. This is a textbook example of what geologists call a boxwork structure. When iron-rich minerals concentrate along fractures and bedding planes in a sandstone rock, sulfate-bearing minerals are left in between. Near the surface the sulfate forms crystals and expands, breaking apart the rock, while the iron-bearing zones remain intact. The differences in weathering create the post office box, cubby-hole appearance.

The trail is an excellent geology classroom; you can see ancient geological history preserved in the rocks along the trail. There’s even a small fossil quarry at Wymp’s Gap between Rockwood and Garrett, where the rock is filled with marine invertebrate fossils between 330 and 360 million years old!

Native Pennsylvanians

The Indians that moved here after the Monongahelas were refugees from the east: the Delawares (Lenape), the Shawnee and later the Iroquois. These were the people French and English traders first encountered.

At first, British colonists stayed on the eastern side of the Alleghenies. But as immigrants kept pouring in, traders, trappers and settlers eventually pushed over the mountains. There were fewer French colonists than English, but the Indians still felt threatened by both groups.

The French and Indian War

France and England had been at odds across the ocean for military and trade dominance for almost 50 years before the colonization of North America. It’s no surprise that their feuds extended into the New World. The French built a series of forts to secure their claim on the interior of the continent. They built Ft. LeBoeuf, near Erie, by the winter of 1753.

The colonial governor of Virginia sent 21-year-old Major George Washington to Ft. LeBoeuf with a letter telling the French to leave. The French commander, a bit sarcastically, sent Washington back to Virginia with a letter saying he would take the matter under advisement.

In the late winter of 1754, the Virginians sent a hastily-organized troop to the Forks of the Ohio (present-day Pittsburgh) to build a fort to stop the French. In April of that year, the French moved in, chased the Englishmen away and built their own fort, Fort du Quesne.

As far as the Virginians were concerned, war had been declared. They sent out now-Lieutenant Colonel Washington with a force of men to recapture the Forks. On his way there, he took a side trip down the Youghiogheny to determine if it could be navigated to the Forks. He camped at the Turkeyfoot, (now the town of Confluence, where the Casselman and Youghiogheny Rivers converge) and turned back when he found the falls at Ohiopyle to be impassable.

The French, sent out a party under Ensign Joseph Coulon de Jumonville de Villiers, brother of the commander of Ft. du Quesne with a letter telling the English to leave French territory. Jumonville is supposed to have crossed the Youghiogheny at Stewart’s Crossing, now the town of Connellsville.

Washington’s Indian scouts found the French first — Washington and his men ambushed the French and Jumonville was killed in the fight. The French declared this an act of war and sent out an army of 900 from Fort du Quesne to avenge the killing. Washington’s troop of about 350 men, built a small stockade up on Chestnut Ridge that Washington named Fort Necessity. There they were surrounded and defeated on a rainy July 3, 1754. The French allowed Washington to surrender with honor, but forced him and his men to walk all the way back to Cumberland.

The ensuing hostilities became known as the French and Indian War on this side of the Atlantic and the Seven Years War in Europe. The war spread across North America, Europe and Asia, where both France and England were trying to establish colonies.

England’s King George II sent General Edward Braddock in early 1755 with two regiments to attack the French at Ft. du Quesne. To move his troops, Braddock built a road through the wilderness. This road later became part of the first National Road, now U.S. Route 40.

Braddock crossed the Youghiogheny twice at Stewart’s Crossing. First going to what he thought would be an easy victory; then coming back mortally wounded after a humiliating defeat by the French and their Indian allies.

(The route of the Great Allegheny Passage overlooks the battlefield in what is now the town of Braddock.)

The war lasted until Brigadier John Forbes methodically and successfully routed the French, built Fort Pitt and named the town Pittsburgh in honor of William Pitt, the Prime Minister of England. The war finally ended with the Treaty of Paris in February, 1763, which demolished France’s hopes of becoming a global power.

Even after the war, smaller battles went on between the colonists, who rapidly moved into the area, and the Indians whom they forced out, culminating in Pontiac’s War in 1763, a desperate effort to drive the settlers back over the mountains. The Indians under Chief Pontiac were defeated at the Battle of Bushy Run on August 5 & 6, 1763.

Immigrants flooded into the area. Indian trails became roads that carried wagon-loads of settlers over the mountains. The rivers became highways carrying flatboats with settlers and goods downriver. Pittsburgh, with its three rivers, became a gateway to the west.

Pittsburgh and the Industrial Revolution

In the 1820s, flatboats gave way to steamboats that could make the river journey both ways. Pittsburgh supplied the coal to fuel the new steamboats and the industry to build them using the abundant coal, iron and timber resources in the area. In the early 1850s, the railroad came to town, bringing reliable year-round transportation that wasn’t dependent on the vagaries of the river.

The railroads demanded huge amounts of iron and steel for their tracks, locomotives, and bridges, and coal to fuel their engines. Mines and mills sprang up to support the new enterprise. Railroads brought raw materials into the mills and took finished goods out, sustaining the industry. Immigrants from all over Europe and the rural South came to work here, bringing diversity into the city.

During the Civil War, Pittsburgh became an arsenal, producing millions of tons of guns and armor. When World War II raged across the Pacific, Pittsburgh supplied seagoing vessels for the war effort.

But after World War II, the steel industry went into a long, slow decline which accelerated sharply in the late 1970s and early 80s. Mill after mill shut down, costing hundreds of thousands of jobs. In the same period, demand for coal not only decreased, but much of the Pittsburgh Coal Seam was worked out, closing mines by the score. Loss of the mines and mills hurt the railroad’s freight traffic and passengers left the rails to ride the new interstate highways and jet airliners.